You can learn a lot about investment strategies by playing math games.

Let’s try one today on Coinbase Global Inc. (Nasdaq: COIN).

See, everyone and their brother is talking about Coinbase. Every analyst has an opinion on whether you should buy or sell the cryptocurrency platform’s stock.

Folks seem to either love Coinbase and advocate for buying as much as possible … or they’re total skeptics, warning us to stay away.

But probabilistic thinking operates in the middle gray area. And I have something to offer in that regard.

So, we’ll play a math game…

Part I: You Must Buy Coinbase (COIN)

Let’s start with the premise that you just have to buy shares of Coinbase. You can’t help yourself.

Fear of missing out (FOMO) keeps you up at night. You count sheep and all your potential profits one … five … 10 years out.

OK, so we’re definitely buying shares of Coinbase.

It’s not a question of if; it’s a question of where. Meaning, at what price will we buy shares of Coinbase?

Here’s the conundrum:

- You could buy shares immediately, only to see the stock sell at a 20%, 30% or 50% discount a few months down the road.

Look, I studied 20 initial public offerings (IPOs), including Facebook Inc. (Nasdaq: FB) and Netflix Inc. (Nasdaq: NFLX). They pulled back an average of 41% before they ever climbed 50%.

I’ll get to my analysis on this shortly … hang tight.

- But (there’s always a but) … if you hold off on buying shares, in hopes of being able to later buy that 20%, 30% or 50% pullback, your risk is that the stock takes off and never looks back!

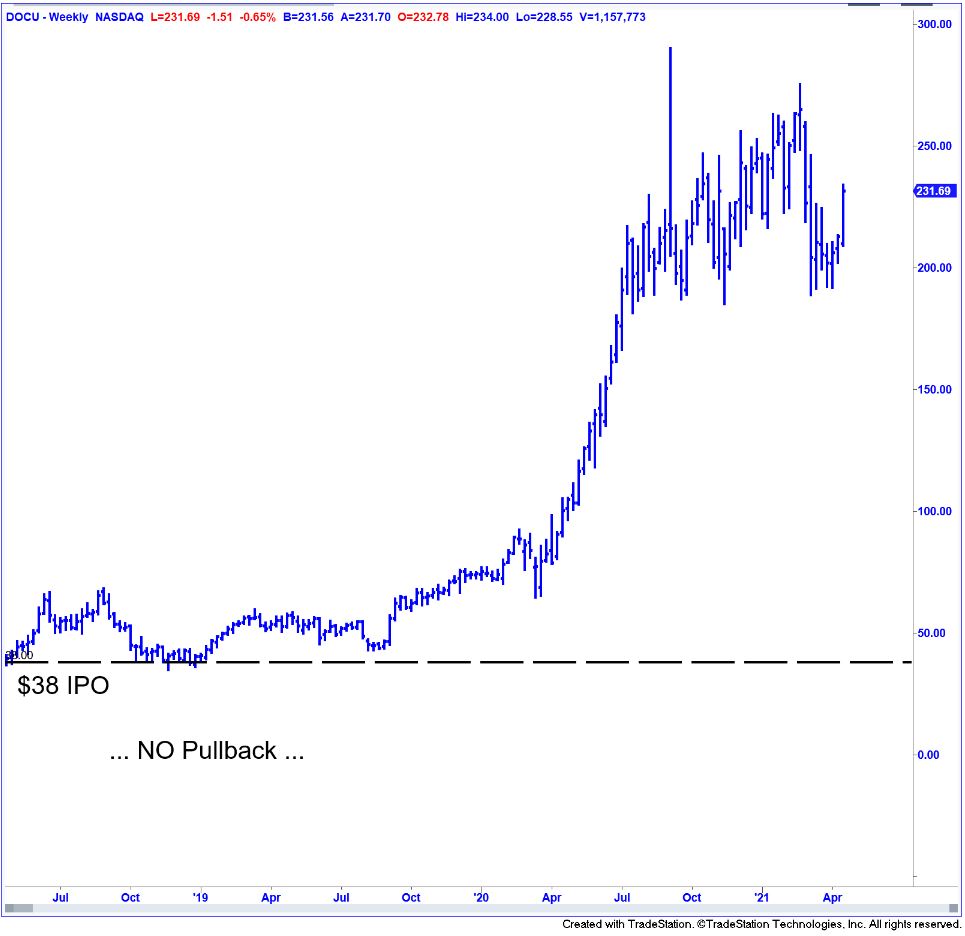

It happens. Google (GOOG) and Docusign (DOCU) are two examples I found.

DOCU Never Dropped

When I traded foreign currencies for a hedge fund, I used what are called Order-Cancels-Order (OCO) “brackets.”

They’re simple: You place two buy orders with your broker — one set at a price above the market and one set at a price below.

When one of the orders triggers and fills, the other cancels.

Sometimes, the market pulls back after you place the order, and you get filled at a cheaper price than you would have if you got in immediately.

But (again, there’s always a but) … other times the market climbs, and you end up paying a higher price.

Back to our Coinbase game…

What if we commit to buying shares of Coinbase with this bracket tactic?

We will:

- Buy shares of Coinbase if they fall 50% from their $381 debut open.

Or:

- Buy shares of Coinbase if they climb 50% from that price.

Of course, scenario A is far more favorable.

But there’s no guarantee that the stock will gift us that opportunity. And we’ve already decided we must get into Coinbase, so we must prepare for the potential that scenario B unfolds instead.

Are we OK with that trade-off?

Is it a good idea, economically?

This Trade on 20 Historical IPOs

I plucked 20 random stocks from the Nasdaq 100 and ran a simple study on them.

First, I made a note of whether the stock first increased or decreased, by 50%, following its IPO.

Out of curiosity, I also tallied and averaged the number of trading days it took for a 50% move (up or down). The average was 119 days, or about 5.5 months, though this isn’t material to whether this strategy is a good idea.

Finally, I calculated two returns for each of the 20 stocks.

The first is the stock’s total return, from IPO “Day 1” until the present. This is the “baseline” result against which we’ll judge my bracket-order strategy.

The second return was either a “discount return,” which was available on the stocks that first pulled back 50% … or a “breakout return,” which was necessary on the stocks that climbed 50% first.

Remember: The bracket-order tactic requires committing to buy the stock at 50% down or 50% up, whichever comes first.

So that’s the key piece of analysis we’re doing on this list of 20 historical IPOs.

I’ve got the answers in the second part of my Coinbase analysis here.

I answer the following questions:

- How often does an IPO go up 50% versus down 50%?

- How much less do you make on an IPO when you have to buy it at +50%?

- How much more do you make when you get to buy it at -50%?

- And, of course, is this bracket-order strategy any better than simply buying the stock immediately?

Stay tuned!

To good profits,

Adam O’Dell

Adam O’Dell is the chief investment strategist of Money & Markets and has held the title of Chartered Market Technician for nearly a decade. He is the editor of Green Zone Fortunes, the trend and momentum options-trading powerhouse Home Run Profits and the time-tested switch system 10X Profits.